Sean Davis gives a haunting first-person account of the inhumanity (and the humanity) of war.

—

Publishers Note: This post first ran in 2012, but it is such an amazing glimpse of the realities of war that we wanted to run it again in honor of Memorial Day 2017.

—

War is a machine designed to lose its parts as it cuts through countries, politics, and peoples’ lives. This machine runs on chaos and in that chaos unnatural and horrible things happen every day. The men that fight in these wars will go one of two ways: they can steel themselves against the toll it takes on their souls or they use it as an opportunity to embrace their humanity. I led eight men through some of the worst parts of combat and took the easy way and hardened anything soft in my mind. I didn’t want to feel, but one of the men in my squad taught me a lesson I would use for the rest of my life, and I didn’t see that lesson until I looked back at the war, months after Eric was killed only three feet away from me in an IED.

Only a few weeks before the ambush, our platoon was out on a mission called a Cordon and Search. Tanks circled the village we called Hamtown since we couldn’t pronounce the real name. Mud huts without plumbing or electricity circled nicer houses the Baathists Army Officers used to live in. They worked on the base US forces were now calling Camp Cooke in Taji, Iraq. The tanks were the cordon, making sure no one entered or exited the village. As leg infantry we were the search element and we had been going from house to house in that intolerable all morning looking for a specific residence. The intelligence we received from the village on the river said the son of an Iraqi colonel who was killed by US bombing was responsible for the recent mortar attacks on base.

By the time we found the right place my entire uniform was soaked through. When I stopped moving to listen to the operations order the intense heat dried the sweat to white salt stains. The LT told Ashford his squad would be doing the initial breech on the suspected terrorist’s house and my squad would filter in next to search the bottom floor.

Ashford blew the lock and they poured into the front door like water.

I sprinted across the dying brown grass of the lawn feeling the weight of the flak vest and all my gear in every leg muscle, the rattle of my squad’s equipment right behind me. A long and terrible shriek came from inside the house, high pitched, but deep and hoarse at the same time, like the screech of an animal. After a few seconds I realized the noise was actually two different screams, one from a child, one from an old woman. The intense fear of having armed strangers unexpectedly burst into the house made the screams louder than seemed possible.

The intolerable heat and the small sprint caused my body to covered with a slick coat of sweat and my helmet slipped over my eyes. I barely stopped myself from barreling into the wrinkled old woman as she wailed in the frame of the front door. I hit her shoulder and to me she felt like a bundle of dry branches wrapped in burlap, hardly felt at all, but she spun around and fell like a clump of dirt-stained robes. I had to keep moving because my whole squad followed right behind me, but the child came running out next, so small. I was able to jump to the side and keep from running over her. Before entering the house I saw the old woman from the corner of my eye gather herself and sit cross-legged with her arms stretched to the sky, eyes closed. The child ran to her, but was ignored, the old woman’s prayers more important than the immediate needs of the naked and dirty baby girl.

She couldn’t have been more than three years old, scared out of her mind. Patches of white sand and tan earth contrasted against her dark skin. Her soiled diaper hung low, almost coming off as she ran around the old woman looking for some attention. The old woman in dusty black robes croaked her prayers to Allah like the child wasn’t there.

I pushed it from my thoughts and continued the mission. The mission was all there was. I couldn’t allow myself to be distracted by emotion, compassion. The front room had vaulted ceilings and a cement floor covered by elaborate rugs, but had nothing else except for long wooden cabinets along each wall with stacks of folded bedrolls, blankets, and pillows on every flat surface.

Third squad sprinted through the front door immediately after us and straight up the stairs to search the floors above. We looked through the piles bedding and found three AK-47s between the pillows. McCreery found eight stacks of one thousand-dinar-bills all with Saddam’s face on them. Matier found what was later counted as twenty–thousand in US currency. I turned to see what the rest of the squad turned up and realized Eric wasn’t inside with us.

“Specialist Zedwick, where the fuck is Eric?”

“I don’t know, sergeant. Outside?” Zedwick said.

A few seconds went by before I could process the fact that one of my men wasn’t doing what I told him. We rushed into the house of a known terrorist and could have faced a squad of men with AK-47s or RPGs and one of my riflemen decided to leave the squad and do what? I shook my head and stared into Specialist Zedwick, Eric’s team leader.

He saw my anger. “I’ll go find him now, Sergeant.”

“Secure this room. Bravo Team search the kitchen. I’ll find Eric.”

I found him standing with his weapon slung in the front yard holding the kid. The sobbing baby’s face pressed up against his flak vest. Her tears made a dark spot in the center of his chest.

I clenched my fists and jaw. “What the fuck, Eric. What if there were armed men in there?”

He gave me that goddamned half-smile he always had ready to diffuse a situation. “You guys would have taken care of them.”

It wasn’t going to work this time. “You are a fucking infantryman, Specialist McKinley. I need you to do your fucking job, and that’s not cuddling war orphans.”

“Sean, come on.” He said, his smile fading.

“Don’t call me Sean. Look around, Eric. Look.” I pointed at the crowd of Iraqis building around the house. “Everyone here fucking hates us. Anyone of them can be the guy we’re hunting. This is a fucking combat zone. I am your squad leader. I need you to do exactly what I say, or someone can get killed. And goddammit, you will call me Sergeant Davis.”

He didn’t answer. There wasn’t anything to say. But I could see it in his eyes: he felt as much as I was trying to not feel. We stood there not looking at each other for a minute or so. Both of us were right and looking at that baby girl clinging to his chest I wished I were wrong.

I left him and the kid and walked over to Lieutenant Kent to give him an inventory of what we found on the first floor. He stood outside of the passenger seat of his Humvee with the hand-mic from the truck’s radio in his ear. I was about to open my mouth when SSG Haney took the butt of his rifle and smashed out a window on the second floor. He poked his head out, looked down at the LT, and yelled, “We have at least a dozen mortar rounds up here, sir. Maybe more.”

There were cheers from inside the house. Lieutenant Kent looked at me. I said, “Sir, we have three AKs, a sniper rifle, a shit-ton of ammo for each, and more stacks of money than I’ve seen in some banks.”

“Saddam bills?” He asked.

“Yes, sir.” I hesitated. “Also American money.”

“US, huh?”

“Stacks of Franklins, also we have a baby, maybe three years old.”

“A baby?” The colonel’s squawking on the radio pulled him away from our conversation. I felt myself blush. Maybe I shouldn’t have brought up the kid. I just wasn’t prepared. While training for combat the idea that there would be babies didn’t cross my mind and now they were everywhere. They should put that in their fucking speech to the new recruits: today’s modern battlefield, not your grandfather’s war, danger linear area at every alley, sniper at every window, etcetera, etcetera, oh, and you can’t do a fucking mission without stepping over teary-eyed orphans that will break your heart by just looking at them.

“Where the hell did you find a baby?” Kent asked.

“She ran out of the house, sir.”

“Not our problem.”

“What about the old lady, sir?”

“Not our problem. If the colonel sees her when he gets here he’ll have her detained and questioned.” Then he was lost to the radio again calling in everything we found so far.

We drove by the detainment area every time we went to the mechanics to get our vehicles fixed, which was about every other day. That place was dark and full of barbed-wire holding areas. No place for an old woman and a baby, but any information she gave us would benefit the mission, maybe stop the daily mortar attacks on the base, maybe avoid the death or injury of American soldiers. I squeezed my eyes tight and the sweat pooled in my sockets and ran down my cheek like a tear. I opened my eyes and breathed the hot air deep into my chest.

I walked with a brisk pace to Eric, slung my weapon across my back, and with both hands out I motioned for him to give me the kid. He held her tighter.

“Goddamn it, Eric. What do you want to do, bring her back to base, enroll her in school, and raise her between missions? Just give her to me we’re running out of time.”

He handed her over even though she fought against it. I carried her kicking and screaming to the old woman still sitting cross-legged, eyes closed, begging Allah for a miracle.

“Hey.” I yelled down at her. She prayed louder. “Hey.” I pushed her shoulder. She didn’t open her eyes. Didn’t stop her wails to Allah. I slapped her hard across her wrinkled face.

Her clouded old eyes opened but didn’t focus for a few seconds.

“Your prayers are answered. Take the kid, go.”

I dropped the girl on her lap and the baby grabbed a hold of the woman tight and buried her head in the folds of her dirty robes. The old lady stared at me confused.

“If you stick around here you’ll be interrogated and detained.” I searched for any Arabic phrase but with all the shit going on I couldn’t find one.

“Lyl byet!” Eric called from behind me. He made a shooing motion with his hands. He was telling them to go away. “Lyl byet.”

The war went on. Eric and I were just parts meant to be lost. Eric died on June 13th, 2004 and I was sent home in a stretcher. I think about him and his goddamned half smile every day and most of the time it hurts like hell, but now I make sure I feel the pain instead of pushing it away.

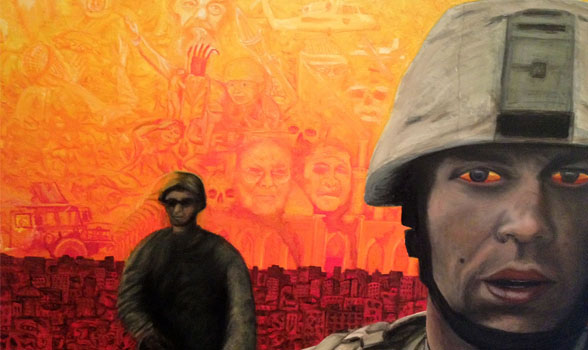

Images— AUTHOR’S NOTE: “The main image is a 4 foot painting my brother Keith Davis painted of me and Eric. Kind of a tribute to his big brother.”

Bottom photo of Eric by Sean Davis.

The post The Breech appeared first on The Good Men Project.